Sebastian Münster, who with his Cosmographia wrote and published what was probably the biggestselling book in the sixteenth century, was actually a professor for Hebrew by profession and only a passionate cosmographer in his free time. Born in Ingelheim am Rhein 20 January 1488 as the son of Endres Münster a churchwarden and master of the church hospital.

Sebastian Münster portrait by Christoph Amberger c. 1550 Source: Wikimedia Commons

Münster’s birthplace Ingelheim from the Cosmographia Source: Wikimedia Commons

He studied at a Franciscan school and entered the Order in 1505. In 1507 he was sent to Löwen and then Freiburg im Breisgau, where he studied under Gregor Reisch (c. 1467–1525), author of the well known encyclopaedic student textbook the Margarita Philosophica, in particular geography and Hebrew.

Ptolemeus and Astronomia from Gregor Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica Source: Wikimedia Commons

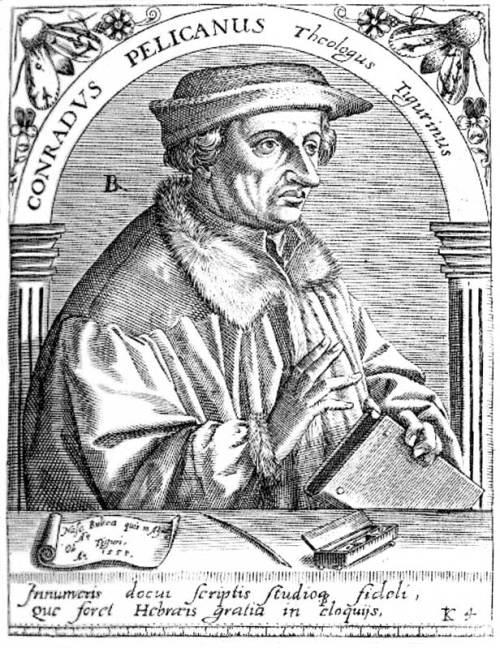

In 1509 he became a pupil of the humanist scholar Konrad Pelikan (1478–1556), who over the next five years taught him Hebrew, Greek, mathematics, and cosmography. In 1512 he was anointed a priest. Pelikan and Münster expanded their studies to include other Semitic languages, in particular Aramaic and Ethiopian.

Konrad Pelikan Source: Wikimedia Commons

From 1514 to 1518 he taught at the Franciscan high school in Tübingen. Parallel to his teaching he studied astrology, mathematics and cosmography under Johannes Stöffler. From 1518 he taught at the Franciscan high school in Basel and from 1521 to 1529 at the University of Heidelberg. In 1529 he left the Franciscan Order and became professor for Hebrew at the University of Basel as Pelikan’s successor, converting to Protestantism. In 1530 he married Anna Selber the widow of the printer/publisher Adam Petri, the cousin and printing teacher of Johannes Petreius. As a Hebraist he published extensively on language, theology and the Bible but it is his work as a cosmographer that interest us here. All of his books were published by his stepson Heinrich Petri.

In 1528 he published a pamphlet entitled Erklärung des neuen Instruments der Sunnen(Explanation of a new instrument of the Sun) in which he issued the following request, Let everyone lend a hand to complete a work in which shall be reflected…the entire land of Germany with all its territories, cities, towns, villages, distinguished castles and monasteries, its mountains, forests, rivers, lakes, and its products, as well as the characteristics and customs of its people, the noteworthy events that have happened and the antiquities which are still found in many places. He gave his readers instructions on how to record an area cartographically from a given point. This is the earliest indication of Münster’s intension to create a full geographical description of the German Empire. This first appeal proved in vain; it would be another sixteen years before he realised this high ambition. Münster satisfied himself with the publication of a small pamphlet Germaniae descriptioin 1530 based on a revised edition of a map of Middle Europe from Nicolaus Cusanus.

Turning his attention to ancient Greek geography Münster published Latin editions of Solinus’ Polyhistorand Pomponius Mela’s De situ orbis. In 1532 Münster drew a world map for Simon Grynaeus’ and Johann Huttich’s popular travel book Novus Orbis Regionum(“New World Regions”, which described the journeys of famous explorers. The map in not particular innovative and does not go much further in its information than the 1507 Waldseemüller world map. However it does contain a border of fascinating illustrations thought to have been created by Hans Holbein, who in his youth had worked for the Petri publishing house.

Münster’s 1532 World Map

In 1540 Münster issued his edition of Ptolemaeus’ Geographia, which was based on the Latin translation by Willibald Pirckheimer. His edition entitled, Geographia universalis, vetus et nova(“Universal Geography, Old and New”) was the first work to contain separate maps for each of the then four continents. In total the work contain forty-six maps drawn by Münster. The world map in this work differs substantially from the one from 1532.

Münster’s map of America Source: Wikimedia Commons

Münster’s magnum opus his Cosmographiaor to give it its full title:

Cosmographia. Beschreibung aller Lender durch Sebastianum Münsterum: in welcher begriffen aller Voelker, Herrschaften, Stetten, und namhafftiger Flecken, herkommen: Sitten, Gebreüch, Ordnung, Glauben, Secten und Hantierung durch die gantze Welt und fürnemlich Teütscher Nation (Getruckt zu Basel: durch Henrichum Petri 1544)

Cosmographia title page

finally appeared in 1544 with contributions from over one hundred scholars from all over Europe, who provided maps and texts on various topics for inclusion in what was effectively an encyclopaedia. Over the next eighty years the work was published in thirty-seven editions, in German (21), Latin (5), French (6), Italian (3), Czech (1) and English (1) (although the English edition is an incomplete translation). The work was continually revised and expanded, the 1544 original had 600 pages and the final edition from 1628 1800. The work was published in six volumes, which in the 1598 edition were as follows:

Book I: Astronomy, Mathematics, Physical Geography, Cartography

Book II: England, Scotland, Ireland, Spain, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Luxembourg, Savoy, Trier, Italy

Book III: Germany, Alsace, Switzerland, Austria, Carniola, Istria, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Pomerania, Prussia, Livland

Book IV: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Russia, Walachia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Turkey

Book V: Asia Minor, Cyprus, Armenia, Palestine, Arabia, Persia, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Scythia, Tartary India, Ceylon, Burma, China, East Indies, Madagascar, Zanzibar, America

Book VI: Mauritania, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Senegal, Gambia, Mali, South Africa, East Africa

Town plan of Bordeaux from the Cosmographia Source: Wikimedia Commons

As indicated in his original call for cooperation, Münster’s Cosmographia was much more than a simple atlas mapping the world but was an integrated description combining geography, cartography, history and ethnography to create an encyclopaedic depiction of the known world.

Chartre under attack from the Cosmographia Source: Wikimedia Commons

In total at least 50,000 German copies and 10,000 Latin ones left the Petri printing house in Basel over the eight-four years the book was in print, making it probably the biggest selling book, with the exception of the Bible, in the sixteenth century. The Cosmographiaset new standards in ‘modern’ geography and cartography and paved the way for the Civitates Orbis Terrarumof Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in 1572, the TheatrumOrbis Terrarum from Abraham Ortelius from 1570 and Mercator’s Atlas from 1595. Despite the competition from the superior atlases of Ortelius and Mercator, the Cosmographiasold well up to the final edition of 1628.

Münster’s Cosmographiais without a doubt a milestone in the evolution of modern cartography and geography and he deserves to be better known than he is. Bizarrely, although they mostly aren’t aware of it, Germans of a certain age are well aware of what Münster looks like, as his portrait was used for the 100 DM banknote from 1961 to 1995, when he was replaced by Clara Schumann.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Reblogged this on Through a lens diary.

Pingback: Saxton and Speed two early Elizabethan cartographers and the Flemish influence | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: The first calculating machine | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: The emergence of modern astronomy – a complex mosaic: Part III | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: The emergence of modern astronomy – a complex mosaic: Part IV | The Renaissance Mathematicus