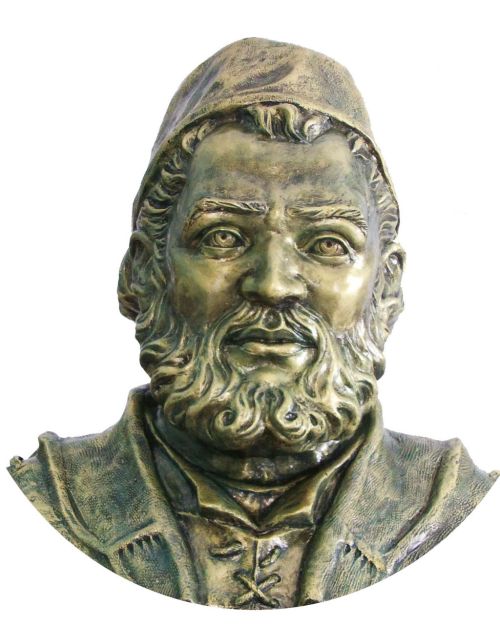

The first substantive history of science post that I wrote on this blog was about the Jesuit mathematician and astronomer Christoph Clavius. I wrote this because at the time I was preparing a lecture on the life and work of Clavius to be held in his hometown Bamberg. Clavius is one of my local history of science celebrities and over the years I have become the local default Clavius expert and because of his involvement in the Gregorian calendar reform of 1572 I have also become the local default expert on that topic too.

All of this means that I have become very sensitive to incorrect statements about either Clavius or the Gregorian calendar reform and particularly sensitive to false statements about Clavius’ involvement in the latter. Some time back the Atlas Obscura website had a ‘time week’ featuring a series of blog post on the subject of time one of which, When The Pope Made 10 Days Disappear, was about the Gregorian calendar reform and contained the following claim:

The new lead astronomer on the project, Jesuit prodigy Christopher Clavius, considered this and other proposals for five years.

The brief statement contains three major inaccuracies, the most important of which, is that Clavius as not the lead astronomer, or lead anything else for that matter, on the project. This is a very widespread misconception and one to which I devote a far amount of time when I lecture on the subject, so I thought I would clear up the matter in a post. Before doing so I would point out that I have never come across any other reference to Clavius as a prodigy and there is absolutely nothing in his biography to suggest that he was one. That was the second major inaccuracy for those who are counting.

Before telling the correct story we need to look at the wider context as presented in the article before the quote I brought above we have the following:

A hundred years later, Pope Gregory XIII rolled up his sleeves and went for it in earnest. After a call for suggestions, he was brought a gigantic manuscript. This was the life’s work of physician Luigi Lilio, who argued for a “slow 10-day correction” to bring things back into alignment, and a new leap year system to keep them that way. This would have meant that years divisible by 100 but not by 400 (e.g. 1800, 1900, and 2100) didn’t get the extra day, thereby shrinking the difference between the solar calendar and the Earthly calendar down to a mere .00031 days, or 26 seconds.

This is correct as far as it goes, although there were two Europe wide appeals for suggestions and we don’t actually know how many different suggestions were made as the relevant documents are missing from the Vatican archives. It should also be pointed out the Lilio was a physician/astronomer/astrologer and not just simply a physician. Whether or not his manuscript was gigantic is not known because it no longer exists. Having decided to consider Lilio’s proposal this was not simply passed on to Christoph Clavius, who was a largely unknown mathematicus at the time, which should be obvious to anybody who gives more than five minutes thought to the subject.

The problem with the calendar, as far as the Church was concerned, was that they were celebrating Easter the most important doctrinal festival in the Church calendar on the wrong date. This was not a problem that could be decided by a mere mathematicus, at a time when the social status of a mathematicus was about the level of a bricklayer, it was far too important for that. This problem required a high-ranking Church commission and one was duly set up. This commission did not consider the proposal for five years but for at least ten and possibly more, again we are not sure due to missing documents. It is more than likely that the membership of the commission changed over the period of its existence but because we don’t have the minutes of its meetings we can only speculate. What we do have is the signatures of the nine members of the commission who signed the final proposal that was presented to the Pope at the end of their deliberations. It is to these names that we will now turn our attention.

The names fall into three distinct groups of three of which the first consists of the high-ranking clerics who actually lead this very important enquiry into a fundamental change in Church doctrinal practice. The chairman of the committee was of course a cardinal,Guglielmo Sirleto (1514–1584) a distinguished linguist and from 1570 Vatican librarian.

The vice chairman was Bishop Vincenzo Lauro (1523–1592) a Papal diplomat who was created cardinal in 1583. Next up was Ignatius Nemet Aloho Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church till his forced resignation in 1576. Ignatius was like his two Catholic colleagues highly knowledgeable of astronomy and was brought into the commission because of his knowledge of Arabic astronomy and also to try to make the reform acceptable to the Orthodox Churches. The last did not function as the Orthodox Churches initially rejected the reform only adopting it one after the other over the centuries with the exception of the Russian Eastern Orthodox Churches, whose church calendar is still the Julian one, which is why they celebrate Christmas on 6 7 January.

Our second triplet is a mixed bag. First up we have Leonardo Abela from Malta who functioned as Ignatius’ translator, he couldn’t speak Latin, and witnessed his signature on the commissions final report. He is followed by Seraphinus Olivarius an expert lawyer, whose role was to check that the reform did not conflict with any aspects of cannon law. The third member of this group was Pedro Chacón a Spanish mathematician and historian, whose role was to check that the reform was in line with the doctrines of the Church Fathers.

Our final triplet consists of what might be termed the scientific advisors. Heading this group is Antonio Lilio the brother of Luigi and like his brother a physician and astronomer. He was here to elucidate Luigi’s plan, as Luigi was already dead. The lead astronomer, to use the Atlas Obscura phase, was the Dominican monk Ignazio Danti (1536–1582) mathematician, astronomer, cosmographer, architect and instrument maker.

In a distinguished career Danti was cosmographer to Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany whilst professor of mathematics at the university of Pissa, professor of mathematics at the University of Bologna and finally pontifical mathematicus in Rome. For the Pope Danti painted the Gallery of Maps in the Cortile del Belvedere in the Vatican Palace and deigned and constructed the instruments in the Sundial Rome of the Gregorian Tower of Tower of Winds above the Gallery of Maps.

After the calendar reform the Pope appointed him Bishop of Altari. Danti was one of the leading mathematical practitioners of the age, who was more than capable of supplying all the scientific expertise necessary for the reform, so what was the role of Christoph Clavius the last signer of the commission’s recommendation.

The simple answer to this question is that we don’t know; all we can do is speculate. When Clavius (1538–1612) first joined the commission he was, in comparison to Danti, a relative nobody so his appointment to this high level commission with its all-star cast is somewhat puzzling. Apart from his acknowledged mathematical skills it seems that his membership of the Jesuit Order and his status as a Rome insider are the most obvious reasons. Although relative young the Jesuit Order was already a powerful group within the Church and would have wanted one of theirs in such a an important commission. The same thought concerns Clavius’ status as a Rome insider. The Church was highly fractional and all of the other members of the commission came from power bases outside of Rome, whereas Clavius, although a German, as professor at the Collegio Romano counted as part of the Roman establishment, thus representing that establishment in the commission. It was probably a bit of all three reasons that led to Clavius’ appointment.

Having established that Clavius only had a fairly lowly status within the commission how did the very widespread myth come into being that he was somehow the calendar reform man? Quite simply after the event he did in fact become just that.

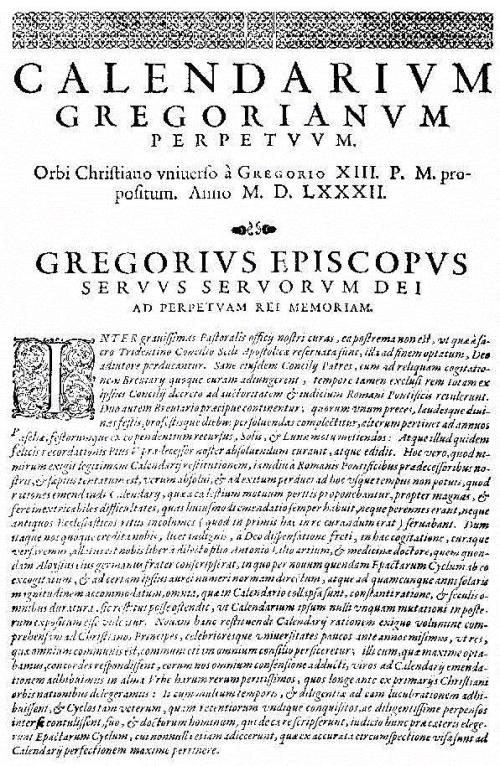

When Pope Gregory accepted the recommendations of the commission and issued the papal bull Inter gravissimas on 24 February 1582, ordering the introduction of the new calendar on 4 October of the same year,

he granted Antonio Lilio an exclusive licence to write a book describing the details of the calendar reform and the modifications made to the process of calculating the date of Easter. The sales of the book, which were expected to be high, would then be the Lilio family’s reward for Luigi Lilio having created the mathematical basis of the reform. Unfortunately Antonio Lilio failed to deliver and after a few years the public demand for a written explanation of the reform had become such that the Pope commissioned Clavius, who had by now become a leading European astronomer and mathematician, to write the book instead. Clavius complied with the Pope’s wishes and wrote and published his Novi calendarii romani apologia, Rome 1588, which would become the first of a series of texts explaining and defending the calendar reform. The later was necessary because the reform was not only attacked on religious grounds by numerous Protestants, but also on mathematical and astronomical grounds by such leading mathematicians as François Viète and Michael Maestlin. Over the years Clavius wrote and published several thousand pages defending and explicating the Gregorian calendar reform and it is this work that has linked him inseparably with the calendar reform and not his activities in the commission.

Heilbron’s delightful book The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories has quite a bit to say about Ignazio Danti, a fascinating figure in his own right. Danti had a remarkable talent for obtaining funding for various astronomical instruments; you might say he excelled at grantsmanship.

Another interesting post! I’ve been trying to show students how history and science blend, and you always have countless examples!

A small detail:

“The last did not function as the Orthodox Churches initially rejected the reform only adopting it one after the other over the centuries with the exception of the Russian Orthodox Church”

There are more churches that did not adopt it: Serbian Orthodox Church, Georgian Church, Jerusalem Church etc.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_calendar#Eastern_Orthodox_usage

And another small point: they celebrate Christmas on Jan 7, not Jan 6.

Thanks ;))

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #33 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Christoph and the Calendar | Life Like a Lego-house

Thony:

Clavius is maybe not a confirmed prodigy, because we know nothing directly about his life before joining the Society of Jesus. But he was likely self taught: we know his instructors in other subjects, but not even Clavius mentions a mathematician in his youth. We also know he was already writing an *expositio* on Sacrobosco’s *de Sphaera* in the mid 1560s, just the same time he began his career as the sole mathematics instructor at the Roman College. His work defending the calendar began a year before his greatly revised *Euclid* came out (1589); in the same busy decade he had made large revisions to the *Sphere* commentary (1581, 1585) and added several philosophical essays to both books. Then there were his ‘white-papers’ for the Society on mathematics curriculum and methods. Smolarski claims they are the first modern examples of the kind on mathematics education. So if not straight prodigy, he was certainly prodigious!

Chris Kirk Speaks

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #32 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Cosmographer to a Grand Duke and a Pope | The Renaissance Mathematicus