We have a novelty here at RM, a guest post. Renaissance Mathematicus Internet friend and historian of science Professor Christopher M Graney wrote asking the assistance of the HISTSCI HULK in demanding justice for the sixteenth century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who had been accused of being a blunderer by a David P Barash in the “Chronicle of Higher Education”. The crew here at RM think the Prof has done a good job of defending the Dane’s honour so we are more than pleased to post his demolition of Mr Barash’s arguments officially endorsed by the HISTSCI HULK.

I recently stumbled upon an old piece in the Chronicle of Higher Education — David P. Barash’s January 3, 2003 “Why We Aren’t So Special” about people’s tendency to see the world in terms of themselves. It centered on Tycho Brahe, the great 16th-century Danish astronomer. In it Barash used the term “Brahean solutions” in regard to “a widespread human tendency: Whenever possible, and however illogical, we retain a sense that we are so important that the cosmos must have been structured with us in mind.” Barash wrote that “Brahe’s Blunder is one of those errors whose very wrongness can teach us quite a lot about ourselves, and about the seduction of species wide centrality.” What was Brahe’s Blunder, according to what is apparently the Chronicle’s only published piece to ever mention Tycho Brahe? It was to recognize the correctness of the Copernican idea that the planets circle the Sun, but to reject the idea that the Earth circles the Sun as well. Thus Brahe argued that the Sun circles an immobile Earth, while the planets circle the Sun. According to Barash, this solution was an ingenious kind of “strategic intellectual retreat and regrouping” that allowed Brahe to “accept what was irrefutably true, while clinging stubbornly to … what he wanted to be true”.

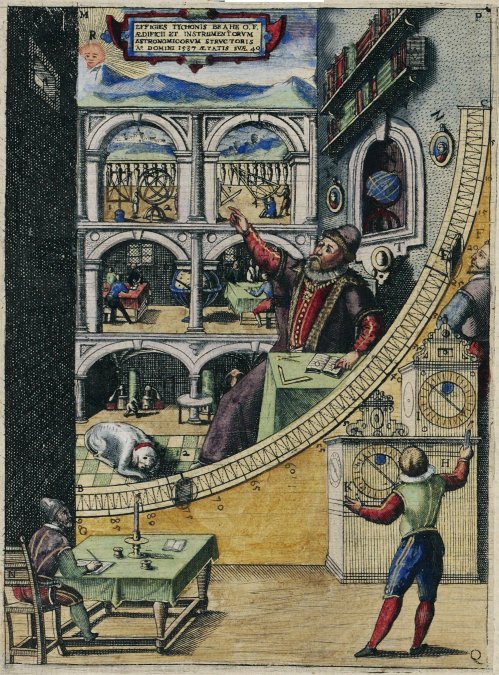

Tycho Brahe’s large mural quadrant at Uraniborg Source: Wikimedia Commons

That is just so wrong. Tycho Brahe deserves some justice — he needs the HISTSCI_HULK to come to his aid! Here is the real story of “Brahe’s Blunder”, and it has lessons to teach us, too:

Barash refers to Brahe as “an influential Danish star-charter” who “achieved remarkable accuracy in measuring the positions of planets as well as stars”. He might as well describe Christopher Columbus, as a sailor who achieved remarkable success in finding some land Europeans didn’t know about. Brahe was the leading astronomer of his era. While other well-known astronomers like Copernicus or Galileo made their observations and published their results and ideas as individuals, Brahe ran a major observatory (“Uraniborg”) and research program on his island of Hven. The cost of Brahe’s program to the Danish crown was proportionately comparable to the budget of NASA. With access to the biggest and best available instruments, and with the most skilled assistants, Tycho Brahe could achieve awesome accuracy in his work: Even though the telescope had not yet been invented in Brahe’s time, he could measure positions to an accuracy of the width of a U.S. quarter coin seen from a football field away; for certain sorts of measurements he could do substantially better. Harvard astrophysicist and historian of astronomy Owen Gingerich often illustrates [for example, see February 19, 2009 – about 10 minutes in] Tycho’s incomparable contribution to the astronomy of his time by means of a thick book by one Albertus Curtius, published in 1666, on the history of astronomical work: Gingerich notes this book contains some tens of pages of pre-Brahean observations, hundreds of pages of material from Brahe, and again tens of pages of post-Brahean observations. Gingerich argues that astronomy would not see a surge in new data proportionately comparable to the one Brahe generated until today’s digital age. He notes that Brahe’s quest for better observational accuracy “places him far more securely in the mainstream of modern astronomy than Copernicus himself”.

One would think such a scientific powerhouse as Brahe could do better than “Brahe’s Blunder”, and indeed he did. Using his naked-eye instruments, Brahe measured the sizes of the planets as seen from Earth. Anyone who is watching the stars this spring – with Venus and Jupiter dominating the sky after sunset while Mars, Mercury, and Saturn all make an appearance – knows from experience that Venus looks a lot bigger and brighter to the eye than does Jupiter, which in turn looks a lot bigger and brighter than Saturn. Using his measured apparent sizes, and the known relative distances of the planets, he calculated their relative physical sizes. His results: Saturn and Jupiter both dwarfed Earth; Mercury was a little larger than the Moon; Mars was larger than Mercury; Venus was larger than Mars but smaller than Earth; the Sun dwarfed all. His results were off — Saturn and Jupiter are larger than even what Brahe calculated; Venus is nearly the Earth’s twin, size-wise; his distance to the Sun was off and so his Sun was too small — but he got the general picture right.

But Brahe did not measure only the planets. Using his naked-eye instruments, Brahe also measured the sizes of stars as seen from Earth. Anyone who is watching the stars knows from experience that Jupiter looks a lot bigger and brighter than the most prominent of stars, Sirius (the Dog star), which in turn looks a lot bigger and brighter than a lesser star like Procyon (the little Dog), which in turn looks a lot bigger and brighter than the faintest stars the eye can see. Brahe measured Procyon to appear roughly the same size as Saturn. If you go out and look at them both (they can both be seen around midnight for most of this March) you can make a rough check of Brahe’s work: They indeed appear similar.

In the traditional geocentric model of the universe, stars lay a bit beyond Saturn, the most distant planet. Assuming that to be the case, Procyon would be somewhat larger than Saturn, although still smaller than the Sun. No problem. But in the Copernican system, the stars had to be immensely far away. This is because Earth moves in the Copernican system, and that motion should be reflected in the stars, but no such “annual parallax” effect was observed in the sixteenth century. The Copernican explanation for this was that the stars are so far away that Earth’s movement around the Sun is negligible by comparison. Well, Brahe knew his measurements were so good that, if the stars were any less than hundreds of times more distant than Saturn, he could detect Earth’s motion reflected in them. And thus, were Procyon several hundred times more distant than Saturn while appearing roughly the same size as Saturn, then geometry would dictate Procyon to be several hundred times larger than Saturn, too. Indeed, Procyon would dwarf even the mighty Sun, like a basketball dwarfs a tiny bead. Sirius would be still more immense than Procyon! Indeed, every single star, even the faintest ones, would dwarf the Sun. The Sun would be the sole bead in a universe of basketballs, beach balls, volleyballs, soft balls, etc.

All the Copernicans could offer against this was something about how the Creator could make all big stars if the Creator so chose: “Who cares how big the stars are?” wrote the Copernican Christoph Rothmann to Brahe, since an infinite Creator God is far bigger still.

To Tycho Brahe, a single bead solar system enveloped in a basketball universe was absurd. Reasonably sized stars made much more sense. To be reasonably sized they had to lie just beyond Saturn, and that required a fixed Earth. Since planets circling the Sun seemed like such a good idea, the logical choice was what Barash has so unjustly termed Brahe’s Blunder — planets circling the Sun, the Sun circling the Earth.

Tycho’s system of the world. Note the stars directly beyond Saturn

Tycho’s system of the world. Note the stars directly beyond Saturn

So why was Tycho wrong? He was wrong because the sizes of stars are illusory. Even a telescope, which will show the true appearance of planets (showing Venus’s phases, for example, as Galileo observed) or the Moon, fails with stars. Two generations after Tycho, Giovanni Battista Riccioli (the Italian astronomer who, among other things, named the features on the Moon such as the Sea of Tranquility where Apollo 11 landed) would update Tycho’s argument using telescopic measurements of the “sizes” of stars. A century after Riccioli, William Herschel (the English astronomer who discovered Uranus) would still speak of stars in terms of “sizes”, although by then he and most other astronomers knew those sizes to be illusory. In the nineteenth century astronomers gained a full understanding of the illusory nature of the appearance of stars — that stars are truly points of light, with merely an appearance of size whose source is the intricate physics of the wave nature of light. But the reasonableness of Brahe’s work was still in common memory. The 1836 Penny Cyclopædia wrote: “The stars [are] spheres of visible magnitude … nobody can deny it who looks at the heavens without a telescope; did Tycho reason wrong because he did not know a fact which could only be known by an instrument invented after his death?” The blundering Tycho who illogically insisted on an unmoving Earth was a myth not yet invented.

And so this is yet another example of what the Renaissance Mathematicus is always pointing out about popular history of science — it is full of wonderful stories that seem to have something to teach us, but that turn out to be myths that we have created to tell us wonderful stories. Tycho Brahe clinging stubbornly to the centrality of the Earth against the advance of science is a wonderful image. Tycho Brahe, the finest scientist of his age, doing precisely what fine scientists do? Comparing rival models against the best available data? That’s just nerdy, boring, and apparently absolutely forgettable.

Still, are we no less obliged than our nineteenth-century forebears to get the story right, and to put away the myth that Tycho Brahe blundered? I wrote to the Chronicle about this. They were not interested. On one hand that is understandable. After all, are they really going to devote space to me writing on minutiae in response to a decade-old piece on a long-dead scientist most people have never heard of, who was wrong? I mean really — who cares? On the other hand, the Chronicle of Higher Education is a journal for an educated audience, and they printed wrong information about a highly skilled scientist. What I have written about Brahe is not widely known (what about Brahe is?) but it can be found in standard sources — for example, Victor Thoren’s Lord of Uraniborg (Cambridge University Press, 1990) has a full discussion, complete with a table of Brahe’s planet sizes on page 304. Was there not an obligation to get the story right the first time, or correct it now?

I believe getting the story right is not just an academic matter. Part of the problem science is having today with various “deniers” is rooted in that which turns Thony Christie into the HISTSCI_HULK. In an article in the January issue of The Physics Teacher I argue that the way history of science is commonly presented conveys an idea that answers in science are easy, and that the wrong answers come from human folly. Thus Brahe becomes the blunderer who didn’t get the answer right because he wanted the Earth to be the center of the Universe. The problem with such myths is that they hide the real difficulty in getting the right answer in science. “Deniers” claim that the real answer is out there, but is being hidden by powerful forces — and they can wrap themselves in the mantle of science “history” with its stories of people who don’t want to see the real answer (like Brahe, supposedly), and who might persecute those who do (“Look what they did to Galileo!”). So the real story, that the most accomplished astronomer of the day argued for an immobile Earth using a darned solid scientific argument, matters. It shows that answers are not easy in science, and that good scientists follow the data, not what they want to be true.

Pingback: The Prof says: Tycho was a scientist, not a blunderer and a darn good one too! | Whewell's Ghost

I was going to correct you, saying that the name of Brahe’s observatory was Uranienborg, but after a quick check realised that it is indeed called Uraniborg by the Swedes. The Swedes are always ruining everything for me…

Thanks once more for saving the day, HISTSCI Hulk!

When are you going to offer the HISTSCI HULK a guest post?

One of these days, if something strikes my fancy, I actually might. Thanks for the offer, Hulkster!

You’d be very welcome

Dear Thony, I recently wrote down a few reflections on Stephen Greenblatt’s recent best-seller “The Swerve: How the World Became Modern” that might make for a suitable offer to the HISTSCI HULK. If you (or the Hulkster) are interested, I could email it to you.

You have my email address mail away

Thank you very much for this guest post! When I first came across one of Christopher Graney’s papers on the arxiv, I was quite excited about what he has to say, and thought that it should been known to much wider an audience.

That the “missing parallax” problem was a very serious issue for Copernicanism actually should be not that difficult to understand today, especially if one makes “naturalness” assumptions to avoid the “hierarchy problem” that the realm of the stars has a scale that much bigger then the solar system. I’m using terms and arguments used in today’s theoretical physics on purpose – l wonder if this can be helpful for today’s scientists to better appreciate the debate back than?

However, I am confused by the formulation that “Using his naked-eye instruments, Brahe measured the sizes of the planets as seen from Earth.”

DId he really measure angular diameters? Or is this to say that he infered sizes from apparent magnitudes, which probably requires additional assumptions about distances?

Sorry if this comment is a bit off-topic – I’m getting back to the issue of “rants” to debunk propagation of myths and errors about the history of science.

Let me first state clearly that I completely agree with the points of the post, and that it’s quite odd to characterize Tycho as an “influential Danish star-charter” etc, and that it is important to try to set the record straight…

That said, I don’t have access to the full text of article at the Chronicle, but from the abstract I would guess that Tycho was not in the “main cast” of the text, which may explain the absence of feedback from the Chronicle

But the main reason for this comment is the following statement from Christopher Graney’s “Physics Teacher” paper (which I appreciate very much, so please, no offense for what follows):

“But who outside of the world of physics has heard of Michelson and Morely—very good physicists who helped set the stage for Einstein with their unsuccessful experiment to detect Earth’s motion through the “ether” (the supposed medium for light waves)?”

Now, as everyone knows ;-), the Michelson and Morely experiment was not substantial at all for Einstein’s path to special relativity – it has even been argued that he had not even known about it in 1905. Though it’s clear now that he did, it’s also clear that it was just one piece of experimental evidence among many, and that it was not decisive for Einstein’s reasoning.

The role of the M&M experiment for special relativity seems to be a typical example of physics textbook “history of science”, maybe not too different even from the Leaning Tower of Pisa story.

Please don’t get me wrong – the last thing I want to do is to embarrass your guest blogger – he may well be fully aware of the actual historical circumstances.

What I want to point out is that there are so many myths out there that we are often not even aware that we are propagating one, if it is outside our own, necessarily narrow, area of expertise. And this is one more reason why I am sceptical in general about “OMG how ignorant they are” rants…

Though I am not sure what is an efficient alternative in order to debunk myths.

Thanks, Stefan

On M & M I personally think Chris’ phrase ‘helped set the stage’ is historically accurate. Ignoring the very open question about how much Einstein knew about M & M and how much he was influenced by it, after he had published his 1905 paper M & M results, which were well known, helped people to accept Einstein’s theory.

As I understand it, Einstein scholars now trace the Michelson-Morley as prelude to relativity “myth” to Einstein himself, who cited it not in his first papers, but soon thereafter as leading logically to his own contributions. He didn’t claim it was at the root of his own thought process. Rather, his citation of it did what most citations do — establish a sort of transcendental narrative of scientific progress. So, to say it “set the stage” would not be incorrect so long as we’re not too concerned with presenting Einstein’s own motivations.

Pingback: The Prof says: Tycho was a scientist, not a blunderer and a darn good one too! | The Renaissance Mathematicus « msponheimer

I enjoyed aspects of this but HISTSCI HULK! It will be a slot on the world service science section next Thony!

I listened to Myths of the Brain last week had an excellent slot on on some experimental work done in Edinburgh with regard to maths and dyslexia. Program was ruined by a presenter with a novelty noise sound track and a ha ha look at the very stupid people and what they think running alongside some interesting material. One coming up a nuclear power in Japan soon that seems to take the same tone. Interesting topic and subject but I won’t be listening.

Getting utterly feed up of being subjected to patronising noises about myth busting that would appear to be developing into something of a media craze that’s very of the moment.

I find it sad that I increasingly turn off the world service when a science slot comes up or don’t read subjects that would normally interest me. I love the stuff you do that makes H.O.S. a part of history, not the aspects that while the history is still interesting and thought provoking, start to look like the bad old days when H.O.S. had no distance from its subject and was simply selling cultural French fries for the heritage science burger industry under the advertising banner Lunatic fringe whig dino history from the land that time forgot.

Its now historical credible but still sits far to close to its subject. Never seen this doing history any good, when it looses the distance it should maintain from its subject; as it can end up playing politics to the extent it seriously looses sight of objectivity. Their are a number of examples outside of H.O.S. where this is a constant danger.

This does not make H,O.S look like part of a vital bigger historical picture I think, it does the opposite, it makes it look very different and adrift.

Sorry for such negative feedback but it’s how I think and feel. I hope I am alone in turning off from the subject in the media as the issues are very serious here. Will keep quite in future on this, stick to reading the history driven posts and avoid the more drama driven hero/ villain capers.

That you as an ethnologist who specialises in analysing myths get pissed off by a craze for ‘myth busting’ is very understandable Jeb. I know exactly where you are coming from; my father wrote books about mythology! I strongly suspect the craze is driven by the success of the American TV programme “The Myth Busters”, which is basically intended as entertainment and which has developed a cult status. Although the programme does has a very high slapstick element it actually rather nicely demonstrates the fundamentals of the scientific method.

However there is absolutely nothing new about my doing myth busting. If you look at the second post ever on this blog my ‘Mission Statement’ you will can read the following paragraph:

However it is the third member of the unholy triumvirate listed in the title that is the main driving force for most of my work and will also provide much of the substance of this blog, the mythology of science. It is considered a prerequisite for an educated person to know the main features of the history of Western science and these are duly taught in our schools, colleges and universities. Unfortunately that, which most people believe to be the principle or outline ‘facts’ of the history of science are not facts at all but myths. What is taught in our educational establishments is not the history of science but the mythology of science. Unfortunately this pervasion of falsehoods is not restricted to polite cocktail party chat but is used by such people as historians and philosophers (of the non-scientific variety) to formulate their theories, leading to some real intellectual perversions. My life’s function as a historian of science is to serve as a myths-of-science buster and one of the principle functions of this blog is to expose and explode those myths.

I would however point out that all of my myth buster posts do in fact contain a lot of real and I hope accurate history of science correcting the errors in the myths.

The HISTSCI HULK is an Internet joke, not of my making, coined by another historian as a graphic description of my sometimes somewhat belligerent but tongue in cheek style. As a lifelong Marvel Comic and especially The Hulk fan I decided to pick up the ball and run with it. If you don’t share my humour there is nothing I can do about it. How long I shall keep the joke going is of course another question. To be honest I have no idea. Come back in three years and the HISTSCI HULK might still be ranting about bad history of science then again he might just choose to disappear next week.

So what is the resolution to the problem Tycho found, then? Looking things up, it appears that Procyon and Sirius are not hugely larger than the sun. So where was his mistake?

Read the paragraph immediately under the diagram!

Excellent post. I don’t know how many times I have pointed this out!

Here I am with Tycho teaching my (then) young son the fundamentals of astrometry on the island of Hven:

Hven is now part of Sweden; a large part of southern Sweden, including Hven, was then part of Denmark. Tycho’s family is rather famous in Sweden for completely different reasons (although Tycho himself is of course famous as well).

Those who believe in the blunder of Tycho often believe that he was so influenced by the Church that he couldn’t conceive of a moving Earth. However, considering that he never married his long-time live-in girlfriend and mother of his children, I don’t think Tycho cared much for ecclesiastical tradition!

A few comments and answers to questions:

First, Stefan’s question of whether Brahe actually measured these values is interesting. In his Progymnasmatum, where he devotes a good bit of space to the issue of star sizes, Brahe writes, “I have discerned by diligent applied inspection” that typical first-magnitude stars are two minutes in diameter. You can see this at

http://www.archive.org/stream/operaomniaedidit02brahuoft#page/430/mode/2up

— it’s in Latin, though (the English is my translation).

I as understand it, two minutes is within Tycho’s ability to measure — I think he claimed to be able to reach one minute in most cases and better in certain cases, and I’ve read modern analysis backing that up. But I’ve not seen a technical discussion of how he made the measurements — I do not know the details of what his “diligent applied inspection” consisted of. But what Tycho is measuring is weird. These sizes are not “real” like the size of the moon is real — they are optical effects, although that was not figured out until much later. But, effects or not, they are something everyone sees. I’ve gotten interested in this question of sizes and have taken to asking people who know nothing about astronomy to look up at a first-magnitude star and the moon and tell me how many stars would fit across the moon. The question is tough, because it depends on how good the eyes are, and whether people have heard somewhere that “stars are points of light” and so forth and are aiming to give the “right” answer rather than the one they see, but answers have ranged from 8 stars to 60 stars — or about 4 minutes to 1/2 minute. And of course measuring this stuff does yield real information as regards the planets — their apparent “magnitudes” may not represent a physical size like Brahe thought, but they do result from distance and physical size, among other things, so the only way distant Jupiter can have the same magnitude to the eye as nearby Mars is if it is a lot bigger.

I disagree with various grousings that Thony or I are just being curmudgeonly about people’s lack of knowledge. Science is one of the most of influential human undertakings, but we know its history so poorly. Here in the U.S., the Civil War is extensively studied by scads of historians. We will know how many men fought in some minor skirmish and who the casualties were, etc. The Civil War spans only a few years, or only decades if taken more broadly. Science spans centuries and, by comparison to the Civil War, it has virtually no one studying it. So what people know is dominated by myths, and in my opinion those myths play a significant role in some of the public and political challenges science is facing right now. And its just not OK to publish wrong information that is out there for the looking (and hey, I think saying Michaelson & Morely, “set the stage” is too vague to be misleading or contributing to myths – I needed to drop a name physicists recognize as being people whose work didn’t pan out as expected).

I apologise for including a link that requires a subscription. A “Duh” moment.

Another location for the The Chronicle article can be found at

http://www.lasalle.edu/~didio/courses/hon462/hon462_assets/evolution_assets/why_not_special_barash.htm .

Great post. I have always been frustrated with the way in which Brahe has been portrayed as a blunderer who took a step backwards on the march towards Copernicanism’s inevitable victory. In a way this masks the incredible contribution that Tycho played in the history of astronomy. Its interesting to note that if you look at appearances in Early English Books Online Key-stroked texts Tycho is quoted and referred to more then Galileo and Copernicus. Which shows that he had a greater legacy during the seventeenth century then he has now.

I wrote a post some time ago that points out that Tycho’s system was the dominant one in Europe in the first half of the 17th century. You can read it here.

Pingback: L’héliocentrisme, cette théorie fumeuse… | Le Webinet des Curiosités

Pingback: Jesuit Day | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: Little things matter – for want of a semicolon. | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Once again an excellent post… I have known most of this, however, I got surprised to learn that the Kingdom of Denmark was giving NASA-sized budget to Brahe. What was the reason? NASA started as a combined military/race-against-communist pursuit, in an age of science…

Pingback: Defending Tycho Brahe | συμποσίον ἀκταῖος κατακηλέω

Pingback: The orbital mechanics of Johann Georg Locher a seventeenth-century Tychonic anti-Copernican | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Excellent post, as always. I would volunteer only one tiny caveat – while it is an obvious (but common) historic error to criticise Brahe’s model in retrospect, it’s also easy to mete out the same treatment to those in favour of the Copernican model. From what little I have read on the subject, my feeling is that all the major actors such as Cop, Kep. and the Gal were well aware of the problem of the size of the stars. They regarded the problem as an awkward anomaly in an otherwise exciting model, that might be later explained – just as we regard problems such as dark energy and dark matter today. (For example, many Copernicans suggested that the apparent size of stars was an illusion, as you know). That some invoked God as an explanation is routinely used to mock the Copernicans, but surely that’s a little bit of a cheap shot: theological explanations were quite common at the time for outstanding enigmas. I think the quote “Who cares how big the stars are?” is a good summary of how many Copernicans saw the issue

P.S. Re AE and the Michelson-Morely experiment: I never understand the quantum fuzziness about this issue. There is a clear and unambiguous citation of the M&M experiment in the first section of the famous 1905 paper. I don’t have it to hand but the phrase is something like; “Many effects, such as the failure to detect the motion of the earth through the ether, lead to the conjecture that….”

I think the debate is about whether the MM experiment was a motivation for developing SR. It is not uncommon, and is considered courteous, to cite previous work, even if it was not involved (or not even known) when the citing work was developed.

P.S. For the anoraks, AE’s citation of M&M is here: first line of 2nd paragraph

http://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol2-trans/154

I should add that AE was remarkably poor at citing relevant works (including his own). In consequence, it is fair to assume that a result cited in his 1905 paper was in his eyes very relevant indeed.

In any case, we need not guess – Einstein’s view of the relevance of the M&M experiment is spelt out in many of his reviews of the road to the special theory – see for example his popular-level book ‘Relativity: the Special and General Theories’ p149 or his later book ‘The Meaning of Relativity’ p27

There’s a new theory out there that argues quite convincingly that what Tycho Brahe unwittingly discovered is that the Sun and Mars (which caused so much trouble and pain for both Brahe and Kepler) are a binary pair. With what we know now about the overwhelming prevalence of binary systems (over 85% of our visible stars are binary double stars), this actually makes a lot of sense… http://www.tychos.info/

I think you are confusing the first of August with the first of April

Sadly, no. The new theory out there is supported by at most a handful of people, is not convincing at all, and doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Pingback: Tycho Brahe e il sistema Tychonico - Universe

Pingback: The TOF Spot: 9. The Great Ptolemaic Smackdown: From Plausible to Proven