One area of what would become physics that developed significantly as a direct result of the translations made during the Scientific Renaissance of the twelfth century was optics. The two Islamic authors whose work had the biggest impact were al-Kindi (C. 801–873) and Ibn al-Haytham (c.965–1040). The two Europeans, who initially did most to make people aware of their work in the thirteenth century were Robert Grosseteste (1168–1253) and Roger Bacon (c. 1220–c. 1292). Before going into more detail, it pays to remember that optics here was still the theory of vision and not yet the theory of the behaviour of and properties of light, a transition that first took place in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. However, with the theories of Ibn a-Haytham as transmitted by Bacon and others with have what would become the first phase of that transition.

Robert Grosseteste was principally a churchman and a theologian but was also a polymath who made contributions to a wide range of subjects. Although Grosseteste became one of the most influential scholars of the thirteenth century very little is known for fact about his birth, up bringing, and education. He is said to have been born of humble parents in Suffolk. He possibly received a liberal arts education in Lincoln. He was active in the household of William de Vere, Bishop of Lincoln, from about 1195. The next real information is from 1225, when he was awarded the benefice of Abbotsley in the diocese of Lincoln. By 1229 at the latest he was lecturing on theology to the Franciscans at Oxford University. Anecdotal evidence says he was Chancellor of the University but his actual title was magister scholium (master of students). Over the years he was awarded various other benefices and a prebend as canon in Lincoln Cathedral. However, in 1232, he resigned all of his benefices retaining only his prebend. In 1235 he was elected Bishop of Lincoln, a compromise candidate following a deadlock under the preferred candidates. He maintained this position to his death and became a highly influential figure in the church.

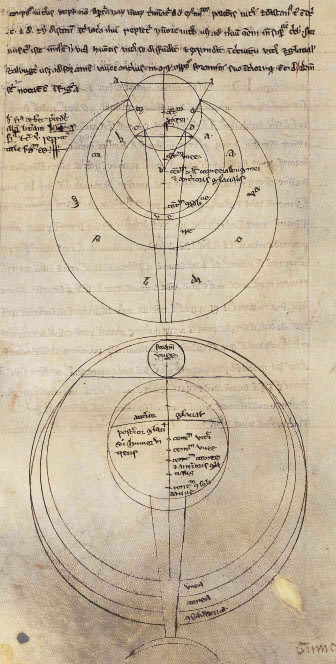

He wrote extensive commentaries on Aristotle and also, having learnt both Greek and Hebrew, became an extensive translator. Important for his influence on the development of optics was the cosmogony that he developed based on al-Kindī’s De radiis stellarum in his De luce self de inchoation formarum and De motu corporali et luce “that everything in the world … emits rays in every direction, which fill the whole world”, in which optics became central, believing light to be the first form of all things, the source of all generation and motion.

Grosseteste’s analysis a light was geometrical, as he wrote in his De lineis, angulis, et figuris (“On Lines, Angles, and Figures” c. 1230):

a consideration of lines, angles, and figures is of the greatest utility because it is impossible to gain a knowledge of natural philosophy without them … for all causes of natural effects must be expressed by means of lines, angles, and figures.

Note, this is three hundred years earlier than Galileo’s over hyped quote from Il Saggiatore.

Grosseteste applies this analysis in detail to both reflection and refraction drawing explicitly in his discussion on Aristotle’s Meteorology and Metaphysics, Boethius’ Arithmetic, Euclid’s Elements. Implicit sources include Pseudo-Euclid’s De speculis, Euclid’s Optics, and al-Kindī’s De aspectibus, all of which he quotes in other works. There is also a hint of al-Kindī’s De radiis in Grosseteste’s assertion that the analysis applies to all natural agents (for example, heat), not just light.[1] Grosseteste and later Bacon regarded light as the multiplication of species.

There is minimal evidence that Grosseteste might have read Ibn al-Haytham’s Kitāb al-Manāzir (Book of Optics) translated into Latin by an unknown translator in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century with the title De aspectibus, but he is a convinced supporter of extramission and not al-Haytham’s intromission.

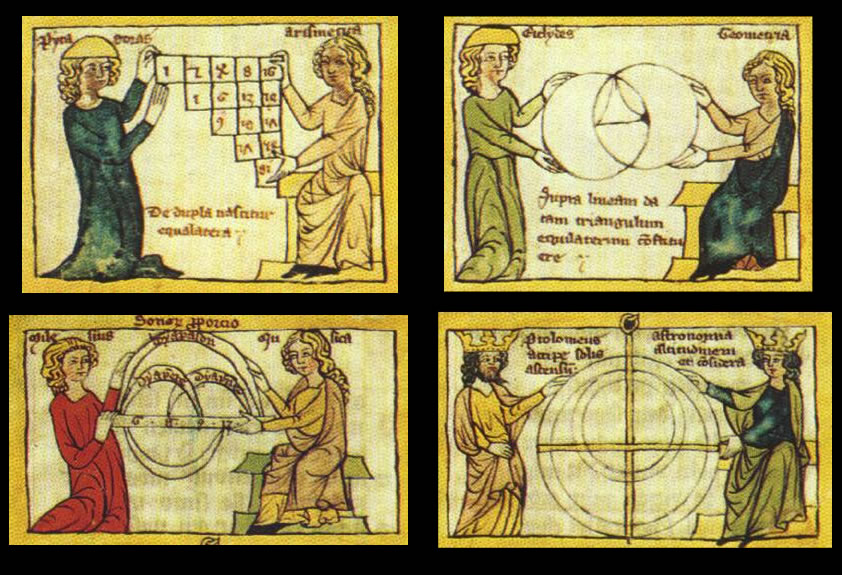

Because light played the central role in Grosseteste’s cosmogony and his major influence in the thirteenth century, optics became part of the quadrivium, that is the mathematical disciplines that formed the second half of the undergraduate curriculum on the newly emerging medieval universities.

Grosseteste was, in some aspects of his thought, surprisingly modern in his approach to science. He strongly believed in the formulation of laws based on personal observation of nature and the use of mathematical to present and explicate those laws.

Roger Bacon is often falsely presented as a student of Grosseteste, but, although, he was very obviously influenced by Grosseteste there is no evidence that they ever met. As with Grosseteste we have a fragmented biography scratched together out of unprecise references. He was born in Ilchester in Somerset of apparently wealthy parents. There are numerous contradictory birth dates. He studied at Oxford probably shortly after Grosseteste had left. He graduated MA in Oxford and said to have taught there. In 1237 or later, he was invited to the University of Paris, where he lectured on the trivium and quadrivium. Around 1247 he left Paris and went wandering through Europe as an independent scholar and his exact whereabouts are unknown for most of the next decade. Somewhere, during that time he meet and became friend with Adam Marsh (c. 1200–1259) a Franciscan and student of Grosseteste, who probably introduced him to Grosseteste’s work. In 1256/7, he became a Franciscan.

As a friar he was blocked from doing or publishing scientific work and he became rebellious and sort a way out of his predicament, sometime in the 1260s taking up contact with the papal legate Guy de Foulques, Bishop of Narbonne and Cardinal of Sabina (1190–1268) hopping for some sort of preferment. Due to a misunderstanding Guy de Foulques, who in 1265 became Pope Clement IV, thought he had already written and prepared for publication a major work and requested to see it. Bacon sat down and produced in short order his Opus Majus, Opus Minus, and Opus Tertium plus several other works in about a year of intense writing. The three Opus volumes are in effect an encyclopaedia of medieval knowledge with his proposals for improving it.

Bacon wrote three treatises on optics De multiplicatione specierum (on the Multiplication of Species), which was probably composed in the early 1260’s. It is an extensive elaboration on Grosseteste’s De lineis based primarily on al-Haytham and it provides the physical foundation for his account of visual perception in his second and most significant optical work the Perspectiva, which is included in part five of the Opus Majus, so composed around 1267/8. Sometime later he composed his third work on optics, the De speculis comburentibus (On Burning Mirrors).

Although Grosseteste and Ibn a-Haytham provided the two main pillars on which Bacon’s theories of optics stood, he also consulted a wide range of other sources that included a-Kindī’s De aspectibus and De radiis, Euclid’s Optics and Catoptrics, Tideus’ De speculis and Pseudo-Euclid’s De speculis. More significantly Ptolemaeus’ Optics and book six of Ibn Sina’s Healing.

His views are close to those of Ibn al-Haytham but are consistently more philosophical and less mathematical and that despite Grosseteste’s influence. Another major difference is that although Bacon, like al-Haytham, believed that visual perception was principally the result of light entering the eyes, thus intromission, he still believed in the involvement element of visual rays emitted by the eyes. Also, whereas, al-Haytham saw his De aspectibus as a finished theory of visual perception, Bacon regarded his Perspectiva as an art prospectus for future research.

Through Grosseteste’s belief in the central role of light in the moment of creation, both Grosseteste and Bacon included a strong element of theology in their accounts of light, and perception.

The movement in the development of optics in Europe in the thirteenth century was taken up by John Pecham (c. 1230–1292). Born to humble parents in Patcham in Sussex, he was educated at Lewes Priory before going to Oxford in about 1250 where he became a Franciscan friar. From here he went the University of Paris where he studied under Bonaventure (1221–1274) becoming a lecturer for theology after graduation. He remained in Paris for many years, where he interacted with many of the leading scholars including Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274). Influenced by both Grosseteste and Bacon he was also active in astronomy and optics.

Around 1270, he returned to England and began teaching at Oxford and was elected provincial minister of the Franciscans in England in 1275. He was soon summoned to Rome and appointed lector sacri palatii,or theological lecturer at the papal palace. In 1279 he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Pope Nicholas III (c. 1225–1280) in opposition to Edward I’s preferred candidate. As archbishop he was a strict taskmaster and, as a result, was not very popular.

He wrote the Perspectiva cummunis with the intention of condensing “into concise summaries the teachings of perspective [perspectiva], which [in existing treatises] are presented with great obscurity.”[2] What he presents is essentially an epitome of al-Haytham’s De aspectibus in three fairly short books. Pecham’s book would go on to become an optics textbook on the medieval university.

The last, and possibly the most important, of the founders of what is know as the perspectivist theory of optics is the Polish scholar Witelo (c. 1230–1280). To quote my own blog post on Witelo’s Perspectiva:

His biography can only be pieced together from scattered comments and references. In his Perspectiva he refers to “our homeland, namely Poland” and mentions Vratizlavia (Wroclaw) and nearby Borek and Liegnitz suggesting that he was born in the area. He also refers to himself as “the son of Thuringians and Poles,” which suggests his father was descended from the Germans of Thuringia who colonized Silesia in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and his mother was of Polish descent.

A reference to a period spent in Paris and a nighttime brawl that took place in 1253 suggests that he received his undergraduate education there and was probably born in the early 1230s. Another reference indicates that he was a student of canon law in Padua in the 1260s. His Tractatus de primaria causa penitentie et de natura demonum, written in Padua refers to him as “Witelo student of canon law.” In late 1268 or early 1269 he appears in Viterbo, the site of the papal palace. Here he met William of Moerbeke (c. 1220–c. 1286), papal confessor and translator of philosophical and scientific works from Greek into Latin. Witelo dedicated his Perspectiva to William, which suggest a close relationship. This amounts to the sum total of knowledge about Witelo’s biography.

If Pecham’s Perspectiva cummunis is the shortened version of Ibn al-Haytham’s De aspectibus, the Witelo’s Perspectiva is the extended version. It is very obvious that his major debt is to al-Haytham’s De aspectibus, although he never mentions him by name. However, Witelo also used Ptolemy’s Optica, Hero’s Catoptrica and the anonymous De speculis comburentibus in composing his Perspectiva, and that he was aware of Euclid’s Optica, the Pseudo-Euclid Catoptrica and other prominent works on optics. Like Pecham’s text, Witelo’s Perspectiva became a standard optics textbook on the medieval European universities. As we shall see in a later episode it also came to play a central role in the transition of optics from a theory of vision to the theory of the behaviour of and properties of light in the Early Modern Period.

Following this burst of activity in the development of optics in the thirteenth century, now known as the perspectivist theory of optics, it became establish as a discipline within the quadrivium at the medieval university. When Regiomontanus (1436–1476) finally was awarded his magister in 1457, the first lecture course he held at the University of Vienna was on optics. However, the discipline rapidly stagnated and there was little in the way of further developments before the sixteenth century.

One should, however, not assume, as unfortunately far too many do, that because of the strong reception in medieval Europe of Ibn al-Haytham’s intromission theory of vision that it now totally dominated the field. There still existed substantial support for extramission theories, such as that of Plato, throughout the medieval period and into the Renaissance.

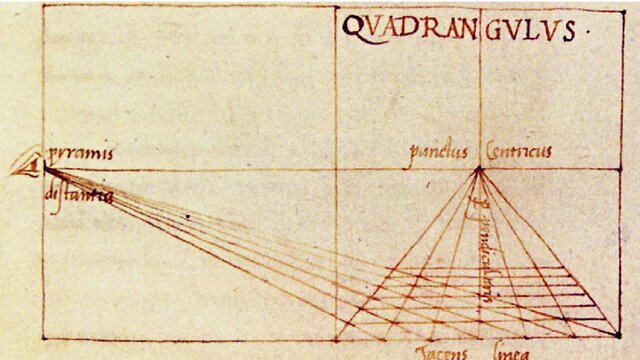

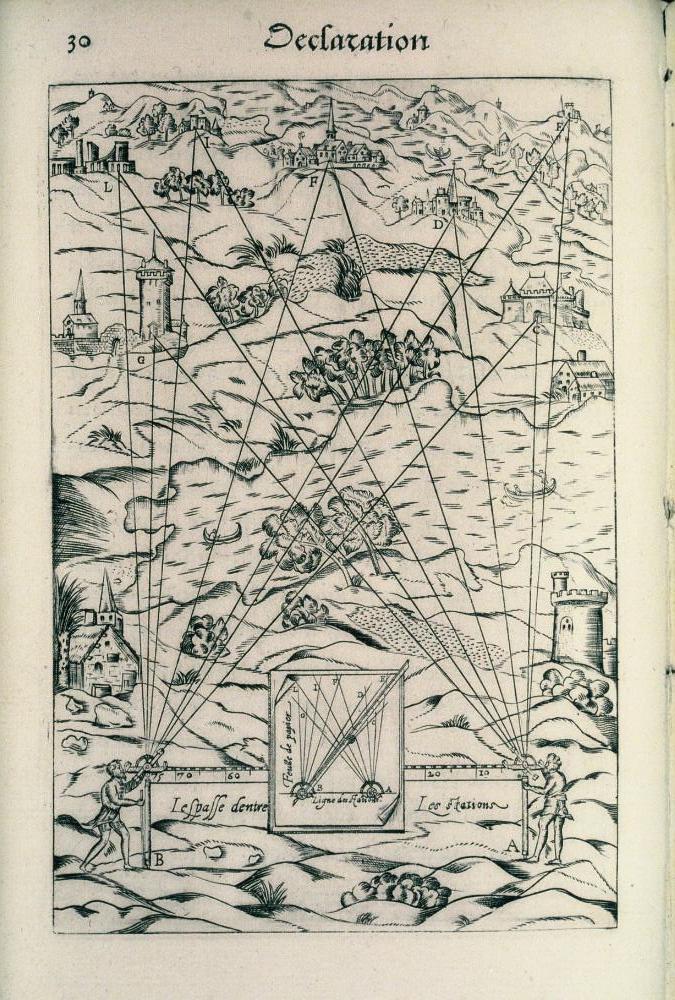

I will close by briefly touching on an aspect of the history of optics that has little to do with its role within physics. In the fifteenth century, linear perspective emerged in European art, specifically in Northern Italy. Some historians, most notably art historians, state categorically that linear perspective was first made possible by the perspectivist theory of optics and more specifically that it owes its existence to the work of Ibn al-Haytham. This hypothesis, and as I will show it is a hypothesis not an established fact, is, to say the least, problematic.

We start with the simple fact that the geometry of linear perspective is entirely Euclidian and the optical theories on which it is based come entirely from Euclid’s optics or the more advanced presentation of it by Ptolemaeus. Nothing added to optical theory by Ibn al-Haytham contributes to the optical geometry of linear perspective. Of course, Euclid’s geometrical optics is at the core of the perspectivist theory.

If we turn to the pioneers of linear perspective there is only very minimal proof for the claim. The earliest, the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), who used linear perspective in the panels of the second set of bronze doors he was commissioned to produce for the Florence Baptistry, dubbed the Gates of Paradise by Michelangelo. Ghiberti wrote an unfinished autobiography Commentarii in which he quotes the Italian translation of al-Haytham’s book, Deli Aspecti. This is the only reference to al-Haytham in the milieu.

We only know about the experiments in linear perspective of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) through hearsay and have no direct information from the man himself, so we can’t say what his influences were.

The first published account of how to create linear perspective in art was by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) in his book On painting, published in Tuscan dialect as Della Pittura in 1436/6 and in Latin as De pictura first in 1450.

Mark Smith thinks that Alberti’s approach to linear perspective is deduced from his work as an architectural historian surveying ancient building and ruins in Rome using a plain table.

A very plausible hypothesis in my opinion. Perhaps even more significant is Alberti’s statement that in linear perspective it is irrelevant with you hold an extramission or intromission theory of vision. Ibn al-Haytham biggest contribution was, of course, combining a Euclidian theory of geometrical optics with a pure, light based intromission theory of vision.

All in all not really a solid basis for appointing Ibn al-Haytham the progenitor of linear perspective.

[1] Adapted from A. Mark Smith, From Sight to Light: The Passage from Ancient to Modern Optics, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2015 pp. 258–259

[2] Smith pp 271–2

Why do you think light was so important to people like Bacon? Historians of science study writers whose work ‘anticipates modern science’ or some such, but others had much to say about light as well.

On the one side light and optics was only one of many subjects that Bacon handled in Opus Majus, as you know better than me.

On the other side, for Grosseteste light was the core element at the beginning of The Creation. In the beginning was the light. So the study of light and optics played a very important role in his theology. This part of Grosseteste’s thoughts was adopted by Bacon. Naturally, historians of science concentrate on the science and usually just mention the theology in passing.

Although there are notable exceptions, among them:

God’s two books: Copernican Cosmology and Biblical Interpretation in Early Modern Science, by Kenneth J. Howell.

The Discovery of Kepler’s laws: the Interaction of Science, Pilosophy, and Religion, by Job Kozhamthadam.

Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist: A Study of Science and Religion in theNineteenth Century, by Geoffrey Cantor.

Michael Faraday: Physics and Faith, by Collin A. Russell. [I haven’t read this one yet.]

Of course, Kepler and Faraday are two religion-infused figures.

What I find striking about the history especially of the physical sciences is the way in which, for instance, optics, is removed from its historical context for discussion because we study optics now. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, and I for one find it inherently interesting. This approach makes a certain amount of obvious sense for early-modern figures, but for medieval ones, I do often wonder whether somebody like Grosseteste would have wondered what in the world historians of science were trying to explain: That we know more about the natural world now than people did in the past? Bacon (who wasn’t so sure about progress), with whom I am most familiar, certainly believed some things we now know to be true. It’s all the other stuff that interests me. The past is a different country.

I’m not sure I understand what you mean. Are you saying that history books about optics don’t discuss the historical context? So by “context” you must mean the social and cultural context, not the context of other works on optics?

In other words, is this about the distinction between internalist history and social history?

Well, different historians are trying to explain different things, if they even regard their job as explaining rather than describing. Not so?

But just about all the histories I’m familiar with also discuss ideas that no longer hold sway. To cite one of the most obvious example, has their ever been an HoS book mentioning Kepler that didn’t include his polyhedral hypothesis? And their are books devoted almost entirely to discarded theories, like Aiton’s The Vortex Theory of Planetary Motions.

I’ll just post one more thing and then leave the topic to others. What used to be called the ‘internalist/externalist’ debate has like so many such issues, morphed into a number of camps and is, mercifully, fizzled out. The Dutchman (as I call my early-modernist husband), distinguishes ‘science heritage,’ by which he means what Roy Porter archly called the ‘pedigree of Truth,’ from ‘science history,’ which is any other kind. Most people produce hybrids. There are no good guys and bad guys here, and one can hope to move beyond the unpleasantly-gendered, heterosexist, racist overtones of old debates. I’m most comfortable talking about scholastic science in medieval Europe. A closing example. Years ago, I was present at an extremely-erudite paper delivered by an ‘internalist’ historian of medieval physical sciences who still walks among us and will not be named. It involved, inter alia, Nicholas Oresme, cosmology, translation (my thing), and the king of France. The audience was reduced to awed silence so I jumped in with the first question to wake people up, asking what importance he attached to the text under discussion being written in French and not Latin. After a few looks from the speaker and others reminding me of how I once felt by accidentally walking into the Gents, he explained that he was only concerned with what the text said and not its language. Moral of the Story: Oresme may have ‘anticipated the findings of modern science,’ but the King of France wanted to hear about his place in the Created Universe in French and he paid the bills. Thereby hangs another tale. The End.

Amen. The social/cultural dimension has certainly enriched HoS considerably.

I’m often struck, especially with the less recent “externalist” works, by a certain defensive posture. They seem to feel they need to claim a significant impact of the social/cultural aspects on what I think you mean by “science heritage”. As if those “external” factors needed that justification, to be studied.

For example, take Geoffrey Cantor’s bio of Faraday. He makes rather unconvincing attempts (IMO) to derive some of Faraday’s scientific ideas from various Bible passages. But the book adds greatly to one’s understanding of Faraday as a complete person.

could you respond to this idiot name Neil God for attacking Tim O’Neil and defending that god-awful book by Catherine Nixie https://vridar.org/2017/10/23/christians-book-burning-temple-destruction-and-some-balance-on-nixeys-popular-polemic/

As I have never read and have absolutely no intention of ever reading Catherine Nixey’s tome, I am hardly the right person to take up arms against Neil Godfrey. Also, Tim is, as he has shown on many occasions, more than capable of defending himself against his critics.

do you know any other good blogs that debunk pseudo history like Godfrey

A good one I just recently ran across (but it’s been around since 2015): Kiwi Hellenist. Subtitled “Modern myths about the ancient world”.